A Series of Dreams: Adventures in the World of Bob Dylan

"All I can do is be me — whoever that is."

Have you heard there’s a film coming out about Bob Dylan, starring Timothée Chalamet? I have, and it gave me pause to reflect on my own history with the music of Bob Dylan. (Don’t forget to check out the Spotify playlist at the bottom of the page!)

One of the big films of the year 2009 was Zack Snyder’s Watchmen. It’s hard to remember now, but this thing was a big deal, leading to a renewed appreciation for the Alan Moore graphic novel of the same name. The film wasn’t very good, but the soundtrack – which I owned on CD – was, featuring tracks by the likes of Billie Holiday, Simon & Garfunkel, Nina Simone, Leonard Cohen, and three songs written by one Bob Dylan. “All Along the Watchtower” performed by Jimi Hendrix; “Desolation Row” performed by My Chemical Romance; and “The Times They Are-A Changin’” played and sung by Bob himself.

“The Times They Are A-Changin’ was played over the film’s opening credits, and up to that point I’d never heard anything quite like it. Just voice and guitar: “stark” is the word I would use. I found it, and Bob Dylan’s voice, unusual but not objectionable, and I filed it away for possible further investigation.

From then on, Bob Dylan began to pop up in my life with increasing frequency. Every place I turned, there was Bob Dylan. I rummaged through my parents’ abandoned record collections and found discarded, sleeveless Dylan albums. I tried playing them, but they seemed wordy and impenetrable. Not long after, I was seated next to a woman at a concert, who told me she was such a huge Dylan fan that she had covered her new guitar in Bob Dylan stickers. Maybe it was time to look into this “Bob Dylan” character.

I picked up a few Dylan CDs from the library (this was early 2013, so this was still a thing people did) and sat down at home to listen. Immediately I was taken with Blood on the Tracks, a kaleidoscopic song cycle from 1975 that wistfully documents a broken relationship, but I also found myself enjoying later albums too: a set of acoustic folk songs called Good As I Been to You from 1992, and Dylan’s then-most recent album, Tempest, which included a 14-minute song about the sinking of the Titanic (because of course). To be honest I wasn’t quite getting it, but I was intrigued enough to continue exploring.

The turning point came when I revisited one of the battered Dylan records found in a box at my mum’s house: the first disc of Bob Dylan at Budokan, a double live album that I later learned had been given a one-star-review by Rolling Stone magazine in 1979. Contrary to that review, I found the album to be the most accessible Dylan record I had encountered so far. For whatever reason I suddenly “got it,” and from that point on, I was a fan.

Who is Bob Dylan? A short answer to that question can be found in the introduction that was read out at the start of his concerts (in a vaguely tongue-in-cheek fashion) between late 2002 and mid-2012.

Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the poet laureate of rock and roll. The voice of the promise of the ‘60s counterculture. The guy who forced folk into bed with rock, who donned makeup in the ‘70s and disappeared into a haze of substance abuse. Who emerged to find Jesus. Who was written off as a has been by the end of the ‘80s, and who suddenly shifted gears, releasing some of the strongest music of his career beginning in the late ‘90s. Ladies and gentlemen, Columbia recording artist, Bob Dylan.

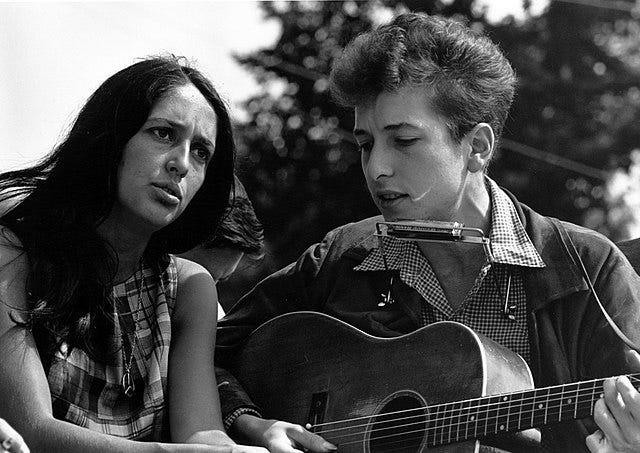

Of course, this slightly odd piece of writing is only part of the story. Bob was born Robert Allen Zimmerman in Hibbing, Minnesota on 24th May 1941, and grew up in nearby Duluth. He acquired a love of music as a child that grew throughout his teenage years, and by 1961 he was ready to journey to New York City to try his luck as a folk singer in the coffeehouses of Greenwich Village. Then followed a dizzying rise to fame that essentially saw Bob become a superstar by 1964, on the back of socially conscious anthems like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Times They Are A-Changin’” that had thrust him to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement. When Martin Luther King spoke from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at the March on Washington in 1963, Bob was there too, having been invited to perform four songs, including “Only A Pawn in Their Game.”

Bob performs at the March on Washington in 1963, introduced by the actor Ossie Davis:

Bob, however, soon began to distance himself from his anointed role as a leader of the protest movement. Before long, he was moving away from topical songs to focus on love songs like “To Ramona” and surreal sonic paintings like “Mr Tambourine Man.” Pushing the boat out further, in 1965 Bob fulfilled his long-held dream of becoming an electric rock ‘n’ roller fronting a band, alienating those who had come to know him as an acoustic folk singer. Bob toured his new music across the USA, Australia and Europe in 1965-66, playing half acoustic, half electric concerts to increasingly hostile audiences, before a mysterious motorcycle accident near his home in Woodstock, New York, put him out of commission for the foreseeable future.

A very different Bob Dylan emerged over a year later, and since then he has more or less done whatever he’s felt like doing, engaged in an eternal struggle to shake off the people who hung their hopes and expectations on him in the 1960s. In 1969 he released a country album called Nashville Skyline. In 1975, he took a ragtag group of musicians on a ramshackle tour that resembled the medicine shows of America’s distant past, calling it the Rolling Thunder Revue. Between 1979 and 1981, he released three albums of Christian music, and played several tours that included nothing but his new religious material interspersed with fire and brimstone sermons.

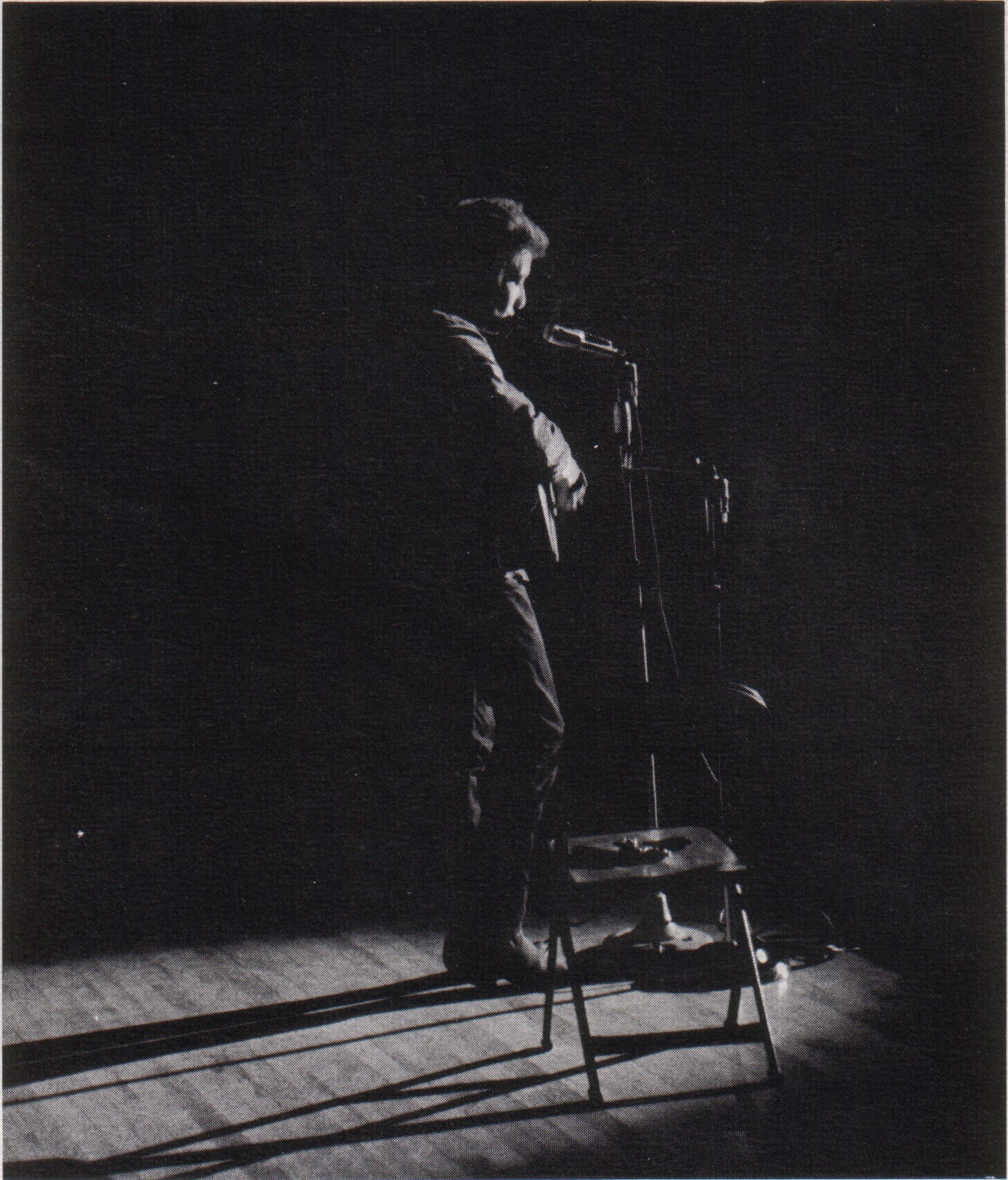

Gospel Bob in 1980:

Dylan has worn many hats offstage too: he’s been an author, a film director, a painter, an actor, a Caribbean schoonerman, a screenwriter, a radio DJ, a whiskey baron, a welder of ornate iron gates, and appeared in TV commercials for the likes of Victoria’s Secret, Chrysler, and IBM Computers. In 2009 he released a Christmas album, which is full of cheer and mirth and the holiday spirit. Bob Dylan might be the world’s finest example of walking to the beat of your own drum, and reinventing yourself when necessary.

Bob meets an IBM Computer:

In 1988, Bob initiated what quickly became known as the Never Ending Tour, which is still ongoing today. Where one tour ended, another would soon begin, and so on and so on into infinity.

An early Never Ending Tour performance of “Masters of War” featuring G.E. Smith of Saturday Night Live fame:

By late 2013 I was officially a fan of Bob Dylan, and decided it might be a good idea to see him live. After all, he was due to play at the Royal Albert Hall that November – what better place to see my first Dylan show? I decided to hit YouTube to find some recent video clips, to get some idea of what a modern Bob Dylan performance looked like.

What I found horrified me. I saw what appeared to be Bob Dylan performing in almost total darkness, singing songs I didn’t know in a voice that was far rougher and raspier than I had heard on even the more recent albums. Even worse, I soon learned that there were no big screens at Dylan shows, meaning that the folks in the cheap seats – i.e. me – would barely be able to see anything. On this evidence, I decided to let the Royal Albert Hall concerts pass me by. Seeing Bob Dylan live was not something I intended to do any time soon.

A little while after the Royal Albert Hall shows, I ventured back onto YouTube to check out what I had missed. The results were surprisingly encouraging: I found a video of Bob singing a haunting song called “Forgetful Heart” to the sound of pin-drop silence from a rapt and attentive audience, a backdrop that became even more noticeable when the sound of Dylan’s piercing harmonica began to reverberate around the grand hall. The voice, too, was much smother than in the previous video I had seen. I was mesmerised. Maybe I should have taken a chance on the show after all. I decided that the next time Bob Dylan came to London, I would be there.

Bob did come back to London in November 2015, to play the Royal Albert Hall once again. And I would have gone, but by this time he was deep into a phase of covering old songs from the Frank Sinatra era, often devoting about one third of his set to this endeavour. I didn’t get this at all, so once again I gave the shows a miss.

Throughout this time, my interest in Bob Dylan’s recorded music was deepening. I discovered albums like Oh Mercy, recorded in New Orleans in 1989, and the epic, cinematic Desire from 1976. For a while, Bob’s deeply unpopular 1990 album Under the Red Sky became my go-to listen every evening when I got home from work. More significantly, during this period I descended into a long bout of depression that lasted through the duration of my 20s, and Bob Dylan’s music provided me with comfort and companionship during what was a challenging time.

It was during this period that, after two missed opportunities, I decided I absolutely had to be in attendance for Bob’s next London appearance. That is if he ever came back to London – he was in his 70s after all. I had been carefully studying concert footage and live recordings, and was beginning to understand what Bob Dylan was doing onstage.

For most popular musicians, the point of live performance is to replicate the studio recordings of their songs as closely as possible. For most people - including me up to this point - the purpose of attending a concert is to hear those studio versions replicated as closely as possible. Not so with Bob Dylan: he might decide that one of his greatest hits needs a new tune. Or how about some new lyrics? Why play it in 4/4 time when you can play it in 6/8? That song was in the key of G? Let’s hear what it sounds like in B-flat. When you go to see Bob Dylan, you’re essentially going to see a man pottering about in his workshop, tinkering with things. You’re watching a process rather than a finished article, and your enjoyment of the show depends on whether or not you're on board with that. Understandably, not everyone is.

But I was! Which is why I found myself heading down to London on Saturday 29th April 2017, to see Bob Dylan perform at the London Palladium. Bob was still deep into his ‘Sinatra phase’ but by this time I was on board with that too – as someone who also has a habit of becoming temporarily obsessed with various arcane subjects (did I ever tell you about the time I got really into Bob Dylan?) I felt I understood. And the show was good! Bob strutted onto the stage in an embroidered suit and a huge white hat, and – accompanied by his five-piece band – delivered a set that contained old favourites, newer songs, and his beloved Frank Sinatra standards, all delivered in the spirit of however he happened to be feeling at that precise moment. I especially enjoyed hearing him play “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Desolation Row.” He didn’t say a word to the crowd all night (more time for music), and eventually he left. I loved it.

It would be two years before I saw Bob Dylan again. This time it was the excuse for a trip to the beautiful city of Kilkenny in Ireland, where Bob was headlining alongside Neil Young in a somewhat decrepit hurling stadium (I was unfamiliar with the sport of hurling before going to Kilkenny, but it’s the thing there, kind of a combination of football, rugby, and lacrosse). Having not travelled much at this time – this was my first trip overseas in nine years – I felt a new world of possibilities stretching out before me. I could plan holidays around attending Dylan shows! Perhaps I could even see one in the USA, or maybe in one of those Spanish bullfighting arenas.

That world of possibilities was abruptly shattered in the spring of 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic turned everything upside down. In lockdown, I was troubled by reports that live music as we knew it would take months if not years to return, and might never be back to what it was. What did this mean for 78-year-old Bob Dylan? I made peace with the fact that I had probably seen him for the last time, and reminded myself that I was lucky to have seen him at all.

In the midst of all this chaos, Bob Dylan was releasing music. In February 2020, he released “Murder Most Foul,” which was 17 minutes long and about the Kennedy assassination (because of course). In March he released “I Contain Multitudes,” which was four and a half minutes long and about himself. This was followed in May by “False Prophet,” which is six minutes long. I have no idea what “False Prophet” is about.

All of this was the preamble to the release of an album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, in June of that year. I had plenty of time to devote my full attention to it, and that attention was rewarded – the album is a portrait of an older man looking back over his life and ahead to whatever’s next. I was particularly taken with the track “Key West,” a long, meandering song that I took to be about finding piece of mind.

Key West is the place to be

If you’re looking for immortality

Key West is paradise divine

Key West is fine and fair

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there

Key West is on the horizon line

The power of music to heal and comfort during times of distress is not touched on nearly enough, and this album was like a warm blanket during this uncertain time. Against all the odds, I hoped that one day it might be possible to attend a Bob Dylan concert again, and maybe hear him play some of the songs from Rough and Rowdy Ways.

Flash forward to November 2021, and Bob Dylan was back on the road. Incredibly, he’d named his new tour “The Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour,” and was playing nearly all of the songs from the new album. As a fan I was delighted, but I was also pleased for Dylan on a personal level. Birds fly, fish swim, and Bob Dylan tours, so lockdown must have been a strange experience for him too.

The “World Wide” tour was at this point stuck in the US, due to varying Covid restrictions in other countries. I had already been toying with the idea of travelling to the USA – for the first time in over a decade – to coincide with my birthday, and had my eye on New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz music and somewhere I’d wanted to visit for many years. Wouldn’t it be great if Bob Dylan was passing through at the same time? Miraculously, he was.

In March 2022, I was in New Orleans. This was the first solo trip I had ever taken, and I was terrified. But I was also excited – I was back in the USA, seeing another Dylan show, and also meeting my friend and fellow Dylan fan Ray Padgett in person for the first time. We visited the house in the Garden District where the Oh Mercy album was recorded in 1989, and Ray also alerted me to the existence of beignets, which you have to try if you haven’t already.

Bob was playing at the grand old Saengar Theater on the corner of Canal Street and North Rampart Street. I was so happy to be there, watching him perform these new songs that he obviously cared deeply about. I didn’t even mind that he was now playing “Key West” – the song I had most been looking forward to hearing – to entirely different music to the album version. Oh well. I was at a live Dylan show again, and everything was as it should be.

Happily, I’ve been fortunate enough to see Bob Dylan multiple times since then, often coinciding my travels with concerts as I had imagined doing in pre-Covid times. I’ve seen him in the UK, the USA, and last year achieved my perhaps oddly specific dream of attending a show in a Spanish bullfighting arena. I was using Bob as a north star of sorts to see the world and become a more confident traveller – and it worked. My fear of flying, and my belief that I would be unable to plan solo adventures, are now things of the past, and it’s partly thanks to Bob Dylan.

All these concerts were different and special in their own way, and I revisit them often in my mind. The only one that bothered me slightly was in Oxford in November 2022. The 81-year-old Bob looked to be in some physical discomfort, which activated my “inner grandson.” I wanted to help – “Are you okay? Can I get you a glass of water? Do you need to sit down?” – but, of course, there was nothing I could do. Fortunately, when I saw him the following year he seemed much more sprightly.

The Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour found its way back to the UK this autumn, making its final stop at – where else? – the Royal Albert Hall. And this time, unlike in 2013 and 2015, I was there too. I had already attended a show on this tour in Nottingham, but when a relatively cheap “gallery standing” ticket became available, I decided to make plans to be present at the famous Hall. I can’t explain precisely why, but I felt that it was important for me to be there.

I had always said to myself that, if I were lucky enough to see Bob Dylan at the Royal Albert Hall, I would like to be in one of the ‘choir’ seats behind the stage, so that I could have a good view of him playing the piano (Bob having mostly given up playing guitar since 2002). I wasn’t in the choir seats, but I did find a spot almost directly above them in the gallery, looming over the proceedings like the Phantom of the Opera. I soaked in the electric feeling that travels around a room in the moments before a Dylan show begins, and then, at the stroke of 8:00pm, Bob’s four-piece band arrived onstage. They launched into “All Along the Watchtower” – one of the three Bob Dylan songs I had first heard on the Watchmen soundtrack in 2009 – and then out walked the man himself, looking like he had just awoken from a satisfying nap.

I spent the next 100 minutes or so watching over the 83-year-old Dylan from above. Some of the songs he had played in the same venue nearly 60 years earlier, in 1965 and 1966, sounding very different now of course. The Rough and Rowdy Ways songs had evolved too, now bearing little resemblance to the album of the same name. “Key West” was now set to entirely different music once again.

And then the show was over. I watched the lights go down, and the silhouette of the impish little figure bobbed along off the back of the stage and disappeared into the wings.

What’s next for Bob Dylan? Maybe he’ll be like Marshall Allen of the Sun Ra Arkestra, and still be onstage when he’s 100 years old. Maybe I’ll never see him again. Or maybe both of those things will be true. I can’t shake the feeling that life has other plans for both of us, and our paths are now headed in different directions.

Having said that, I’d like to invite Bob Dylan to play a show in my hometown of Bedford, Bedfordshire! That’s not as far-fetched as it might seem: the Bedford Summer Sessions series of outdoor concerts has brought big names to my humble hometown in recent years, including Tom Jones, Nile Rodgers & Chic, and Sting. Bob’s unusual performance style would go down like a lead balloon in this environment, which he would probably enjoy, and I would be delighted to give him a tour of the John Bunyan Museum.

If for some reason this doesn’t happen, I’d just like to say that sharing a space with Bob Dylan, on multiple occasions and in multiple locations, has been nothing less than a joy. The circle has closed, and all my dreams have come true.

Are you Bob-curious? If so, I have created what I hope is an accessible introductory Spotify playlist, which you can find below. Merry Christmas!

Beautiful piece. You got into Dylan through BUDOKAN? And you spent a while addicted to UNDER THE RED SKY? No wonder we get along.

My friends and I memorized all the words to most of Bob Dylan’s songs when they came out. I still know all the words to “Like A Rolling Stone”. Thanks for this great piece. I am contemplating seeing the new Bob Dylan movie when it comes out. I usually don’t like actors playing my favorite performers in movies, with the exception of Austin Butler playing Elvis. If you see it when it comes out, I believe Christmas Day, would love your review.